Knowledge Hub

Why is Covid-19 so dangerous for refugees and displaced people?

As lockdown measures gradually lift here in the UK, elsewhere millions of refugees and people living in the world’s most fragile places are still in the midst of their struggle against Covid-19. This article explores why the virus has a disproportionate impact on people living in places suffering from war and instability, and what we can do about it.

Covid-19 knows no borders, and leaves few places – and lives – untouched. However, its impact is hardest for people already in vulnerable situations before the pandemic hit, in particular, the millions of people on the move around the world, fleeing their homes and seeking safety from conflict and instability both in their own countries and across borders.

A new, silent threat

Imagine having to leave everything behind to keep your family safe, only to face a new, silent threat: Covid-19. This is the reality for people living in tents and makeshift shelters in places like Syria and Somalia.

Over 80 per cent of the world’s refugees and nearly all the world’s internally displaced people are hosted in low- and middle-income countries. Many are now living in crowded refugee and displacement camps with little access to medical care, clean water or enough food, making them extremely vulnerable to coronavirus.

In these places, Covid-19 is likely to be even more deadly than it has been anywhere else.

A number of contributing factors

There are a number of reasons that Covid-19 is particularly dangerous for refugees and other people displaced by conflict or persecution.

Access to health facilities and other basic services

For people on the move or living in refugee and internal displacement camps, there is limited access to health services. Even if there are health facilities present, often these do not have the staff or equipment to cope. There are not enough basic hospital beds available, let alone enough intensive care beds, oxygen or ventilators needed to treat the most serious cases of Covid-19. Somalia has just 20 ICU beds in a country of over 15 million people. There is also a severe shortage of trained health workers, and personal protective equipment (like masks and gloves) to keep health workers safe.

People on the move also lack access to other basic services – such as water and sanitation or nutrition. In Somalia, it is common for people to use ashes to clean their hands, as there is no soap available, which is not an effective way to prevent the spread of Covid-19. This coupled with malnutrition and chronic ill health, means that the virus is likely to have a higher mortality rate in these places than anywhere else.

Cramped living conditions

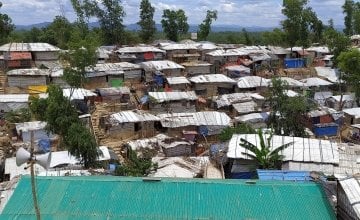

In the Rohingya refugee camps in Cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh, population density averages 40,000 people per square kilometre, but increases to 70,000 in the most cramped areas. Syria, Somalia, and South Sudan is similar, with hundreds of thousands of people – having fled or who are fleeing conflict – taking shelter in crowded settlements and camps.

These cramped living conditions make social distancing extremely difficult, if not impossible. How can we ask people to self-isolate when they live in cramped tents with ten other people? The environment within these camps is, unfortunately, highly conducive to the spread of the virus.

Hunger and nutrition

Many refugees and those internally displaced already do not have access to enough food, resulting in high levels of malnutrition. In South Sudan, 61% of the population do not have enough to eat.

The 2020 Global Nutrition Report stated that “undernourished people have weaker immune systems, and may be at greater risk of severe illness due to the virus”, and severe acute malnutrition in children may worsen its effect.

What can be done to help?

There is potential for an enormous humanitarian catastrophe if Covid-19 takes hold and spreads further through regions in Africa, the Middle East and southern Asia. However, measures can be taken to prevent the spread and help those who are facing this new, deadly threat.

We are responding to Covid-19 by keeping our essential programmes running wherever possible, and supporting local and national prevention strategies to minimise the impact of Covid-19.

For example, our teams are helping vulnerable communities in Somalia by:

In Cox’s Bazar:

- Ahead of the restrictions last year, we distributed a double ration of food to the Rohingya community to ensure families had adequate provisions

- We have redesigned our childhood and maternal nutrition services in the camp to ensure that we do not bring groups together and keep contact to a minimum

- We have increased public awareness campaigns on hygiene promotion and infection control

You can help too.

Your support could help provide therapeutic food for malnourished children, food vouchers to feed a family, or give people the means to set up their own garden so they can access nutritious food during this hunger crisis.

If we don’t act now, there is the potential that more people will die from hunger due to the pandemic than the disease itself. Will you help save lives?