Knowledge Hub

Consequences of the climate crisis in northern Kenya

Last week, the International Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) declared that the climate crisis is damaging the ability of land to sustain humanity.

A further report, released by Christian Aid, laid bare the unjust reality that the people who are most vulnerable to these impacts are those who are least responsible for causing them. In Turkana county in northern Kenya, both of these facts are clear to see as recurrent droughts have led to an escalation of human suffering.

The Horn of Africa is in the grip of drought. Large parts of Kenya, Ethiopia and Somalia have experienced insufficient rainfall for two consecutive rainy seasons, with devastating consequences for people living in those areas due to lost crops and livestock deaths. Food prices have increased and the number of people across the region who don’t have enough food to eat has reached 12 million.

Two droughts in three years

Recent coverage by The Irish Times has detailed the impact of the current drought on communities in Somaliland. This is the second drought in three years that people in the area have experienced.

The same is true for the people of Turkana, a semi-arid county of northern Kenya.

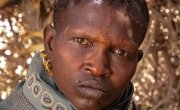

The pastoralist communities who live there are nomadic livestock herders who are reliant on rain not just for their water supply, but to ensure good pastures for their livestock. Already vulnerable communities simply do not have enough time to recover from the losses incurred from one drought before the next drought hits.

Relying on wild fruits for survival

Ng’ikario Ekiru is a 37-year-old pastoralist. She became the head of her household when her husband became disabled due to injury. Of her six young children, three are severely malnourished. As the land has dried up, so too have her options for keeping food on the table.

She used to have a herd of 100 goats. However, in 2017, extreme drought wiped out half of her herd. With little time to recover in between, this current crisis has left her with only five goats remaining. With no pastures for them to graze on, all five have stopped producing milk. The family had relied on that milk as their primary source of nutrition. Now, she, her six children and her five goats all rely on the same source of food - a wild fruit that grows in the bush.

When the wild fruits are there and they are ripened, the animals and I consume them and that is what has kept us going all this time. It takes a short while for the wild fruits to ripen again. When it is gone, it pushes us to the extreme.

When there is no fruit to pick, Ng’ikario has no option but to turn to the animal hides that line the floor of her home, a small round hut made from wood.

“I turn to the old hides and skins. I roast them and that is what we consume,” she explains.

Going days without food

Atiir Kataboi is also a pastoralist. She has seven children and her two youngest are both malnourished. She has also lost her goats to drought. Five were lost in 2017 and the remaining five were taken by this year’s drought. All she has left are three kid goats which are not yet mature enough to produce milk. She too picks fruit for her family and her goats to eat. Atiir tries to supplement this diet by collecting firewood and burning charcoal every day, so that she can sell them to make money to buy food.

“Unless I go and get firewood or burn charcoal, I have nothing else to rely on,” says Atiir.

It is a precarious means of survival. Atiir and her children are eating only one meal a day from the money she earns. If anything prevents her from going about those activities on any given day, they won’t eat at all. Sometimes she finds she is just too hungry and weak, lacking the energy to even move. The reserves of strength she has to draw from to ensure she can put some food on the table are unfathomable, as the changing climate has pushed her to the extreme.

My energy levels are always down. What I do in the morning is get up, take warm water and then tie a piece of cloth around my stomach. Then I will go to the centre, ask someone can I even get half a kilogram of flour, and I will then go and bring them firewood, as a barter trade.

On occasion, she has gone without food for days to make sure her children get some little bit to eat.

I can starve up to ten days without food. I cannot remember the number of times I have stayed without food. All I would take is warm water and sometimes, when it becomes too much in my stomach, I would vomit the water. Because there is nothing to hold it in my stomach.”

Detrimental coping strategies

Not only does it take a toll on Atiir and her own health, but coping measures like this take a toll on the local environment, further degrading it in what becomes a vicious cycle.

Amina Abdulla, Concern’s Country Director in Kenya, explains that when people’s recovery time in between droughts becomes diminished, so too do the coping strategies they can turn to.

“Your coping mechanisms, which include support from relatives and sharing amongst communities, become diminished and you see communities resorting more and more to negative coping strategies. Some of these are actual drivers of the climate conditions that they are experiencing. Things like selling charcoal or firewood involve cutting down trees, it means degrading the environment further just to make ends meet or to survive.”

Increasing frequency of droughts

While droughts can occur in almost all types of climate and are not a new experience for people living in semi-arid terrains such as Turkana, what is new is the frequency with which they are happening. It used to be that they would occur maybe every 15 or 20 years. However, from the late 90s onwards, this cycle was reduced to every five years and over the last decade, it has reduced to every second year. Very simply put, this does not give anywhere near enough time for families to recover and is placing them in increasingly desperate situations.

“The recovery period has become shorter or almost non-existent. If people lost their livestock or their assets and had years to re-build, then recovery might be possible. But when it is every second year, you lose more each cycle. Your ability to bounce back becomes less and less. So it has made people more vulnerable and deepened levels of poverty,” explains Amina.

Certainly for Atiir, she remembers a time when life was easier and her surrounding environment much less hostile.

I remember when I was growing up, there used to be plenty in this land. We used to drink milk, we used to eat meat and we had a lot of harvest from the forest. Life was so good. But now, things have really changed since the drought came in … it has cleared all the animals, all the livestock, the fruits of the land. The trees have also withered, there is nothing that comes from them. Everything has dried up.

Concern is responding

Malnutrition rates in Turkana have reached 30% in some areas with this current crisis. To put that into perspective, rates of 15% or higher are considered a ‘critical emergency’ situation. The strain it is placing on local health services is immense. Concern started programming in Turkana last year and is working to support malnourished children and pregnant and breastfeeding mothers. We are working with the Ministry of Health and with partners such as Save the Children to reach more mothers and children with vital nutrition support and to strengthen the local health systems that are in place to enable them to better cope with the demand for increased services that comes with recurrent drought.

Ng’ikario is hugely appreciative for the support that her three malnourished children have received. It has come as a huge relief for her.

If I didn’t receive this support, I know my children would have been dead by now.

However, she knows that she needs more assistance if she is to have any chance of survival in the long-term. Even rain can’t help her now. She has already lost too much.

“The rains will not assist me that much. The rains will only bring me water to drink. But I don't have animals anymore to rely on. If I had a lot of goats, I would say my life would be good. But I have no hope for anything good… I have no hope for a better future. All I know is if this tree dries up, I will perish,” she explains.

Funding is urgently needed

Concern has been operating in the neighbouring county of Marsabit for over six years. Amina Abdulla says the type of programming we have implemented there is urgently required in Turkana. In addition to emergency nutrition response and health system strengthening, programmes in Marsabit have aimed to build the resilience of local communities to the shocks brought about by drought. Emergency activities such as cash transfers are combined with longer-term activities such as rehabilitating water systems, rehabilitating lands that have been degraded to ensure there is ample pastures for livestock and diversifying sources of income and food to reduce the reliance on livestock. However, this is a huge undertaking and requires time, funding and other resources in order to be effectively implemented.

You can help people on the frontline of the climate crisis

As the climate crisis escalates on a global level, vulnerable communities around the world are confronting the consequences. All predictions indicate that their situation will only worsen unless action is taken now to enhance their resilience. They urgently need our support. Local strategies are available, such as those that are being implemented in Marsabit county. We are reaching as many people as we possibly can, but we need your help to reach more.