Knowledge Hub

World hunger levels: cause for optimism or alarm?

It’s a question we get asked often - why after more than 50 years of working to end world hunger are there still so many people going to bed on an empty stomach?

After all, Concern and many others have spent the past half a century responding to food crises around the world, pioneering new ways to treat childhood undernutrition, supporting vulnerable communities to be more resilient and better prepared to face future food emergencies, informing nutrition policies and advocating for investment. Why then does hunger persist in our world?

Fewer people going hungry than 50 years ago

Let’s start with the good news. Over the past few decades, the global trend was heading in the right direction - downwards, although it was variable. It dropped from a record high of over a billion people in the early 1990s to around 783 million in 2014. That meant 200 million fewer people were chronically hungry.

While it might sound like a modest reduction, at the time, it gave many people cause to be hopeful for the future.

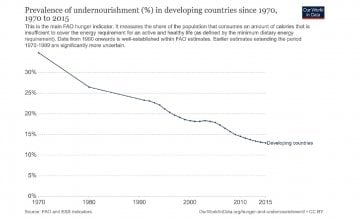

When you look more specifically at the prevalence rate of hunger - that’s the percentage in proportion to world population, and by far the best indicator of hunger - it brings it into even sharper focus. The number of people in the developing world who were undernourished almost halved during that period - from 23 per cent to around 13 per cent.

Even further back, and while reliable sources of data only began in the 1990s, estimates from the 70s suggest that hunger rates fell by a significant 20 per cent in the 45-year period from 1970 to 2015.

A drop in world hunger by a fifth surely gives us room for optimism? On the one hand, yes. Marked progress has been made - there are far fewer people going to bed hungry tonight than there were half a century ago.

Changes to the way we measure global hunger

The big question is - where are we today? To answer that we’ve got to take into account recent changes to the way in which world hunger levels are calculated.

In July, in what was a significant shift, the UN’s definitive annual report on nutrition and food security revised global hunger rates downward - not just for 2019 - but all the way back to the year 2000. The revision was based on more accurate survey data from 13 countries, including China.

It now means that over the past two decades substantially fewer people were hungry compared to what we had previously thought – reducing rates roughly by 100 million. The recent revision means that 690 million people are currently undernourished, which equates to one person in every nine on the planet.

Hunger levels are rising

While it is a positive step that estimates have been adjusted down, there has been no change in the overall trend. That’s a sobering observation. After steadily diminishing for decades, the prevalence rate of hunger has been more or less stagnant since 2014 - and worse still, the actual number of people going hungry has been rising ever since, year on year.

Fuelled by an increase in instability and conflict in fragile countries, and more frequent extreme climate events, along with economic slowdowns and downturns, which all affect access to food for the poor, our efforts to end world hunger are being seriously undermined in ways no one could have anticipated decades ago.

On current trends, world hunger numbers are projected to increase to 841 million in 10 years’ time, putting in serious jeopardy the UN development target of Zero Hunger by 2030. And when you figure in the impact of Covid-19 on vulnerable communities, the worst-case scenario is that hunger levels could peak at more than 900 million in a decade, according to the UN report on The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World (2020).

It is an alarming prediction that would set us back 30 years, and erode many of the life-saving gains made in intervening years. By 2030, instead of celebrating the elimination of world hunger, we could be looking at far higher levels of undernutrition than faced today.

Past reductions show that it is possible to beat hunger. The current upward trend emphasises the need for us to redouble our efforts, so that hundreds of millions of people no longer face the prospect of surviving another day on an empty stomach.

Lives are on the line, right now. Please help us tackle the Covid-19 hunger crisis and save children’s lives.

Other ways to help

Donate now

Give a one-off, or a monthly, donation today.

Join an event

From mountain trekking to marathon running, join us for one of our many exciting outdoor events!

Buy a gift

With an extensive range of alternative gifts, we have something to suit everybody.

Leave a gift in your will

Leave the world a better place with a life-changing legacy.

Become a corporate supporter

We partner with a range of organisations that share our passion and the results have been fantastic.

Create your own fundraising event

Raise money for Concern by organising your own charity fundraising event.